Going Deeper: Post-production – part one

By tom@longhaulfilms.com in Going Deeper

This post is part of an ongoing series called Going Deeper where we look at branded content production through the lens of the world’s most important question: why.

We’re back from hiatus and hope you all had a fabulous festive season and a positive start to this new decade. Before the break, we were looking at what the branded content process looks like and had made it all the way through pre-production and production. Now we’re ready to pick up with post-production, which we’ll cover in a couple of different posts.

Post-production: When everything comes together.

Unlike narrative projects where the script lays out exactly what should go into the final edit, documentary-style projects like this are a little more exploratory in post-production. Of course, in pre-pro, the Director documented exactly what the anticipated story would be, but until the interviews are completed, this is an educated guess, and there is room for unexpected surprises; for example, sometimes interviewees share something they haven’t spoken about during the pre-production process, but which is, in fact, relevant to the story. And the editor, in collaboration with the Director, may decide to include it as it enhances the final product.

The paper edit

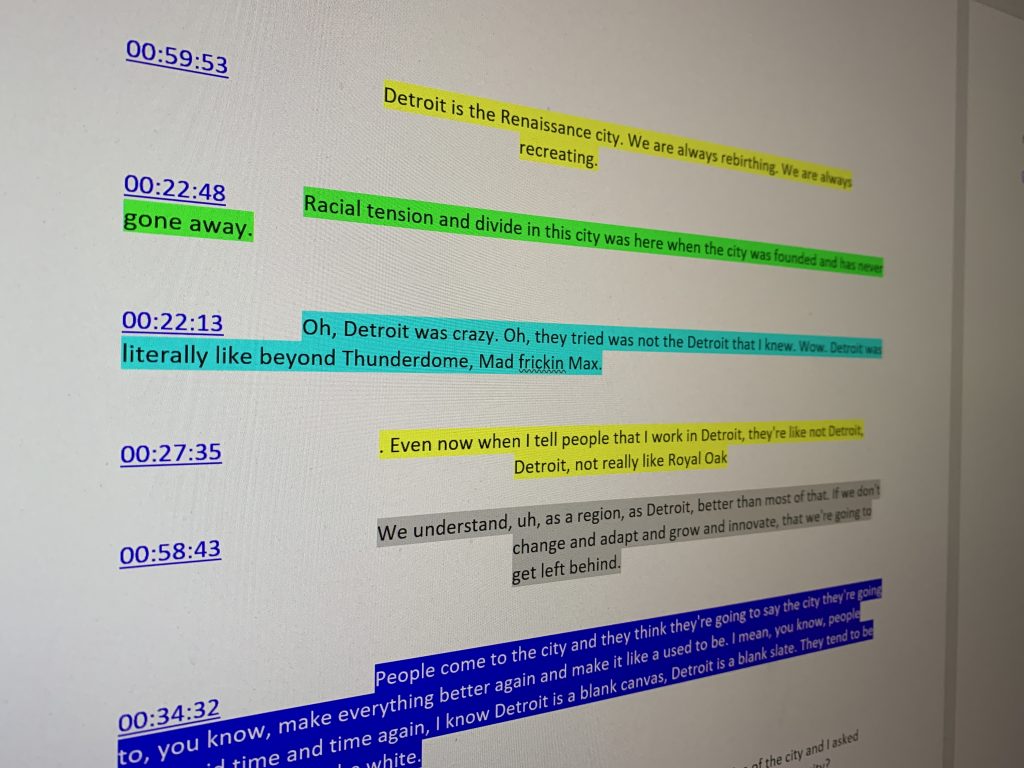

One of the first things that happens in post-production is that the audio from all of the interviews is sent out to a transcription service, who take the audio, transcribe it to text, and send back a document that lists out everything each interviewee said, time-stamped throughout.

The Director can then take all those transcriptions and put together a paper edit – literally a new document with quotes copied and pasted from each interviewee and assembled into an order that makes a coherent story.

The first assembly

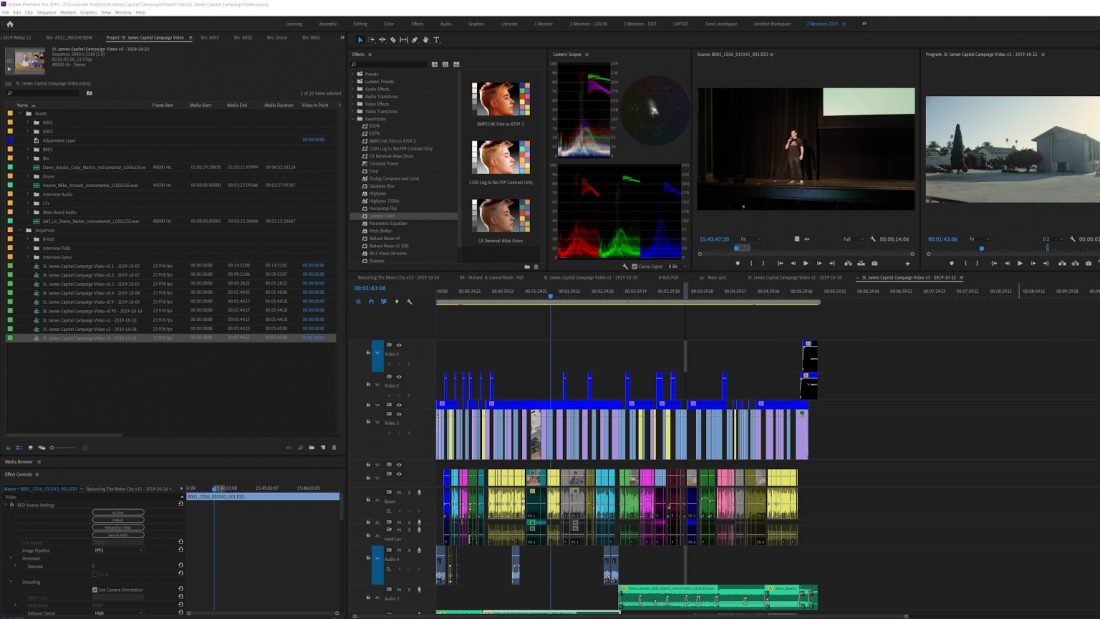

The Editor’s first job is to cut together the interviews per the Director’s paper edit. This is called the first assembly and will go back to the Director for review.

What is not always clear on paper are things like intonation, stutters or overall interviewee performance, so the Director will watch the first assembly with the editor, and make alterations, additions or subtractions as necessary. Often the first assembly will be too long, so part of this process will be to cut the edit down to length.

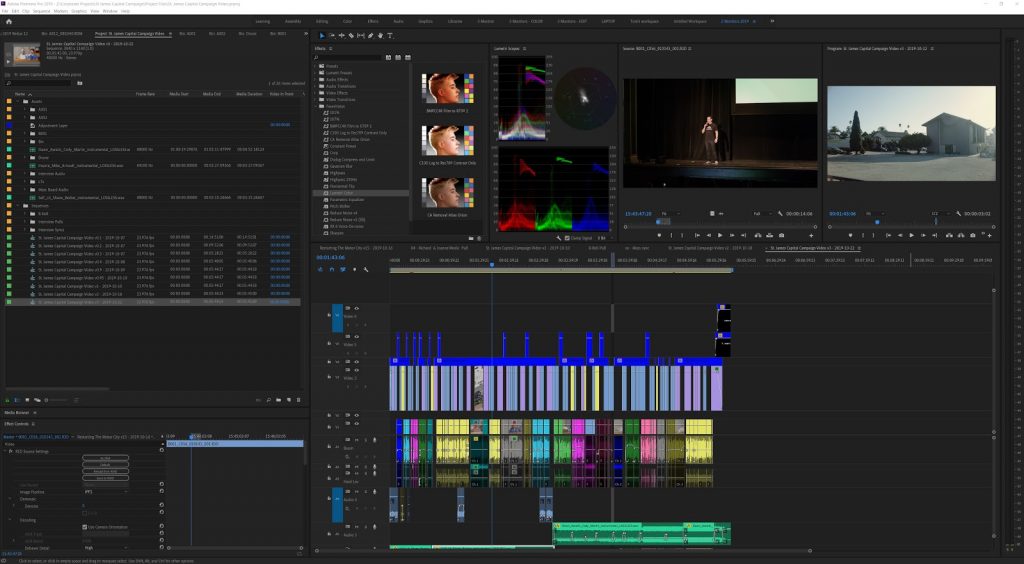

Rough cut

Once the first assembly has been edited for content and length, the editor can then add b-roll and music to produce the rough cut. It’s “rough” at this stage because the audio tracks won’t be totally balanced out, nothing will have been done to the color, brightness or contrast of the visuals. Some imagination is required for someone viewing the rough cut to be able to extrapolate what the final video will look and feel like.

Depending on the client’s experience with video production – and ability to exercise the imagination needed here – the production partner may decide to share the video at this rough cut stage, with caveats about aspects of final polishing that have yet to be implemented. The advantage of this approach is that any larger changes that the client requests can take place before all that polishing work has been done on sections that might now end up on the cutting room floor. The risk is that the rough cut usually doesn’t have as much emotional oomph as it will once everything’s polished up, and it’s easy to mistake this lack of polish for a more fundamental issue with the edit.

Next week we’ll continue the overview of post by looking at music selection, sound mixing and the color grade.